January 2024 - Words on the Page

One of my new favourite pictures of Marian. Wrapped in fur, dripping in silver jewellery, surrounded by ikat dyed textiles, and framed by rock posters. This photo is a behind-the-scenes shot from a photoshoot the late Dennis Collins did of Marian.

January gone, and good riddance to it. That month felt like it took forever. The day job has been crazy in January so there’s only so much to report here for my monthly newsletter but that doesn’t mean nothing got done!

Writing

At the beginning of December, my supervisors requested I produce a draft of all my research so far, as reported in my last newsletter post. The prospect was daunting, because it required me to bring together a lot of ideas and vague understandings to create something structured and reliable. This is, of course, the point of the exercise and I’m very pleased to say that it went well.

At the end of Jan I submitted 6000 words to my supervisors and it’s currently with them for review and commentary. We’ll be discussing their thoughts in mid-February, and I’m sure I’ll have plenty to say about it in the Feb newsletter. Going into it I can already tell you there’s some holes in my research you could drive a truck through, but that’s to be expected after only four months. My writing centred around a few specific areas I felt I understood well enough to make some stronger statements:

Dress/Craft/Art Theory

Always a tricky subject, and bringing any position to the front means annoying a lot of people who have a slightly different interpretation of the line between art and craft. I regret I haven’t yet come up with a truly strong statement, but began with a series of definitions that other academics have proposed and I found to be good enough for my purposes. The point of my research at this stage isn’t to radically redefine decades of craft theory, so for the time being the usual definitions are sufficient.

Broadly, art is self-sufficient/contained, representational, and avant-garde in one respect or another. Craft is an object-based refinement of physical technique and mastery that express aesthetics while also creating a utilitarian object. Art is not required to be encapsulated in an object, nor must it be useful.

There are further considerations in the approach to studying garments/textiles historically. Do we approach them through the lens of the object telling us about the time/practices (this is typically called the “history of dress”) or do we take theoretical ideas and movements and use objects to support or refute these ideas (this is typically called “fashion theory”). The blended approach of “material culture of fashion” allows for a two-way exchange of these concepts and that’s what I’ll be using, courtesy of Georgio Riello. Not all of Marian’s work is fashion of course, but the principle is the same.

Methodology

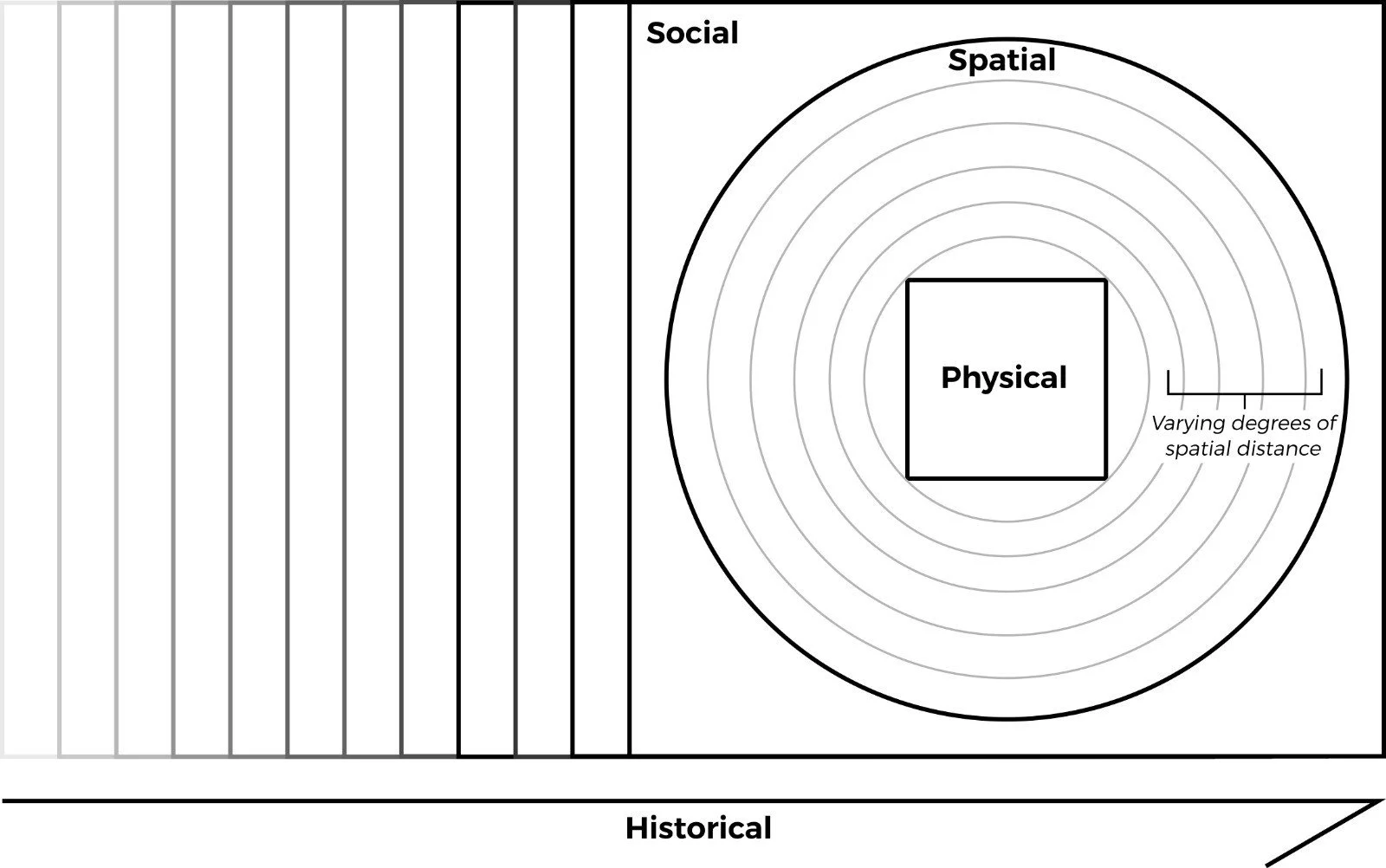

By examining and combining several existing systems for studying objects, I tried to come up with my own! It needs polishing but what I have so far is that all objects have the following aspects defining their significance and allowing for comparison between them:

1) Physical

Maybe obvious, but this is the physical reality of the object. How big is it? What is it made out of? What shape is it? What condition is it in?

2) Spatial

All physical objects exist somewhere in space. Where they exist gives us more information about the object. Layers of increasing distance from the object can also help us compare nearby objects, or the distributions of identical objects/mass-produced objects to get a sense for the significance of the object. A Roman coin sitting in the soil under the Forum in Rome is pretty expected. A Roman coin found in an ancient Chinese tomb gives it a very different significance.

Put another way, and to borrow Schoeser’s example, a spinning wheel on its own doesn’t give us a huge amount of information. Set in a historic house amongst other period objects, it helps tell a story about the time it was made/used and becomes much richer in its ability to give us information

3) Social

All interpretations of objects, from their design through their creation, use, and destruction are socially informed. The object may symbolically represent something (like a crucifix necklace) or be a work of art intended for individual interpretation. The way the object changes interpretations between peoples and cultures also supports the cultural information we can learn from the way it was made and used.

There’s lots more here about how objects are valued and exchanged as well. Some objects are designed for commerce and exchange (like gold bars or air fryers), but others gain special significance to individuals or whole groups of people. These ‘priceless’ objects can range from the extraordinary (the Mona Lisa) to the mundane (your grandmother’s hair brush that she brushed your hair with as a child). The function is the same: the object is more or less likely to be exchanged.

There is also a really important conversation around the art vs utility aspect to the object. Some objects are pure art (see again the Mona Lisa) while others are purely utilitarian (every roll of toilet paper in your house). All of them are designed, but where objects fall on that spectrum helps us classify and compare them.

4) Historical

Finally, all objects have a history, no matter how long or short. Time as an element of change is critical to understanding these objects as they move in space or change hands between people and cultures. I produced the below diagram to try and illustrate this point.

Dress History - Surface Design/”Tie-Dye”

Finally, I tried to start pulling together some of the basics of the literature around tie-dye. What I’ve discovered is that while many of the original makers at the time Marian was active and tie-dye was popular in the 60s/70s used original language names for the techniques of resist-dyeing (e.g. ikat, plangi, tritik) the idea of “tie-dye” seems to have taken all the inspiration from indigenous and ethnic practices, and homogenised them into a Western practice. This has led to a material loss of cultural significance and around the origins of resist-dyeing practices where designers, or indeed makers, believe that tie-dye arose as rainbow shirts during the hippie era as a form of psychedelic art.

In no way does this cheapen the inspired and beautiful creations of artists and craftspeople both in the 60s and today as they look to create tie-dye, but it does highlight an ongoing trend in the appropriation of foreign techniques to satisfy the desire for novelty in the Western art tradition. While the hippies may have had genuinely compassionate and culturally motivated reasons for adopting the dyeing practices of other cultures, tie-dye today is seen as a nostalgic and passé form of dress, associated with the late 1960s and early to mid 1970s. This trend continues in fashion history as the need to drive consumption in fashion required innovative designs, and designers increasingly began to look to foreign cultures for novelty not previously considered in the Western fashion tradition. Picking cultural costume or methods of dress out of their original context for use in the modern Western fashion cycle perpetuates this cycle of taking long-established practices and binding them very firmly to a point in time.

Given Western supremacy on the world stage for both the capitalist economy and dominating cultural influences, this is rarely a positive thing for the originating culture.